A visual story of human inaction towards climate change adaptation

Photos and text: Mohsen Anvaari

WE WILL BEAR WITNESS to this moment in history. This “glocal” media project feature stories from earth's citizens, recording climate destruction, devastation, resilience and hope. WE WILL BEAR WITNESS is a community project and pays contributors lifetime dividends. Pitch us to donate or contribute.

Mohsen Aanvari is a self-taught outdoor and documentary photographer based in Norway. His work concerns the environmental crisis and social inequality, hence choosing photo stories which combine elements of environment, outdoor life and social justice. He continues his research into environmental justice through his photography and documentary work.

A visual story of human inaction towards climate change adaptation

While environmental activists constantly warn us that climate change is happening rapidly, and in the scale of history, they are right, psychologists and neuroscientists believe that from the viewpoint of the human brain these changes are happening slowly—so slowly that it does not trigger proper action from most of us! The human brain computes and reacts very fast to a rapid object coming towards the head. Even though, it is not wired to react properly to threats such as climate change that happen at a slow pace and on a geographically large scale. Therefore, in handling our relationship with environmental issues, we are exposed to several cognitive biases.

These biases lead to decisions that might be beneficial for an individual in the short term, but are collectively often not rational and, therefore, accumulate harmful results in the long term. It is, hence, very essential that in the human-environment relationship, the responsibility of decision making and its consequences gets removed from the shoulders of individuals and gets done by institutes and organizations that have holistic overview on the ecosystem, its ecological capacities and climate trends. In any region where that holistic view towards the ecosystem and its ecological capacities is absent, individuals have no choice than to make decisions intuitively, and they often do so until they lose the battle to the climate change and limited ecological capacities of the region.

In this photo reportage, I am narrating the story of one of the thousand regions in the planet that have faced the effect of climate change on their ecosystem, and where the people have a bitter fate in their lack of holistic view and long-perspective management.

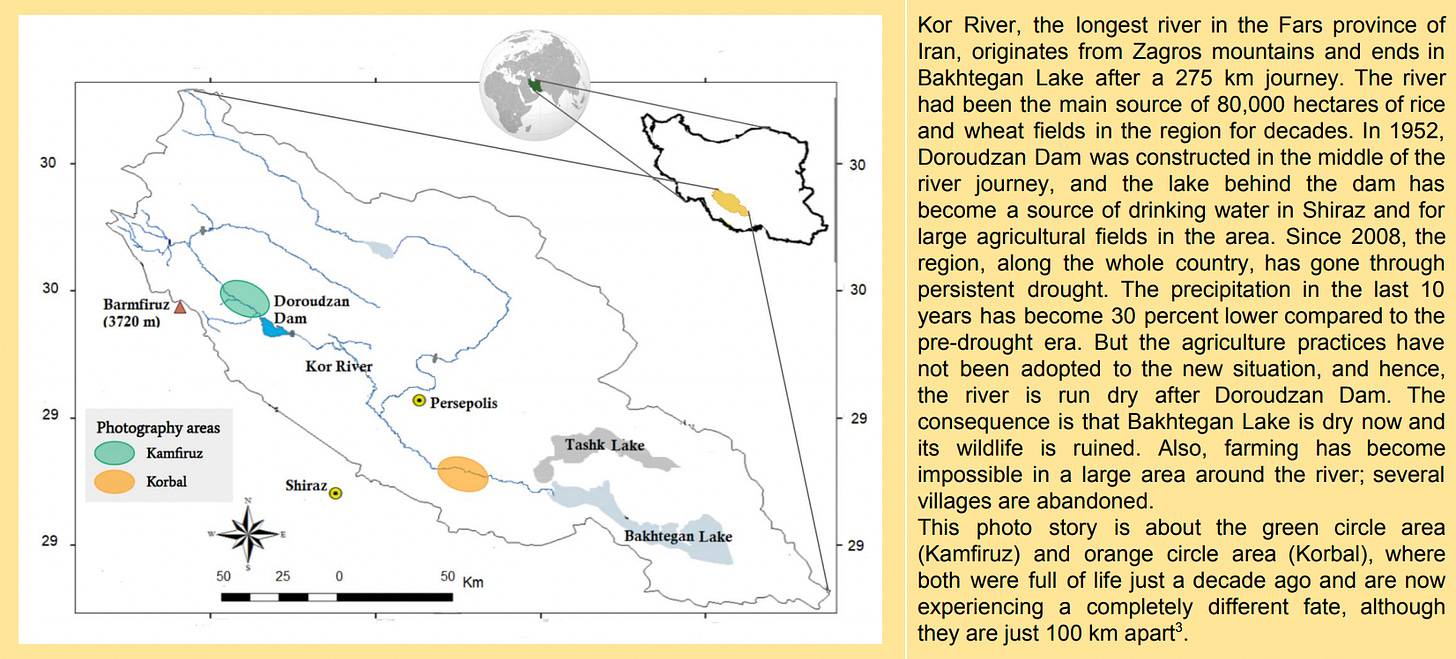

Kamfiruz Plain, at an elevation of 1,700 m, in the middle of June 2019. The mountain in the background is Barmfiruz with a 3,720 m elevation, and it receives the highest amount of snow in Fars province during the winter time. Kor River originated partially from that mountain, then it goes through Kamfiruz Plain and reaches Doroudzan Dam. Around 30,000 people are living in Kamfiruz and they are mostly farmers. More than 6,000 hectares of land in this region are two crops (wheat and rice), meaning that the farmers do stubble burning to the wheat fields and use the land for rice at the same year, which leads to overconsumption of water resources.

A farmer is stubble burning, after harvesting wheat.

The atmosphere around Doroudzan Lake is very polluted in June. The fields are getting ready for planting rice.

The end of Kamfiruz Plain where Kor River reaches Doroudzan Lake. In the middle of June 2019, all fields are in a flooded condition, some have been rice planted already and the rest will be until the end of June. The volume of Dorudzan Lake is 960 million cubic metres, in which 330 million is the sustainability volume, and that part should never get used. Last year, after 10 years of continuous drought, the amount of water reached 334 million cubic meters, only 4 million over this threshold. 35 million cubic meters of drinking water in Shiraz is sourced from Doroudzan, which made the water management very challenging last year.

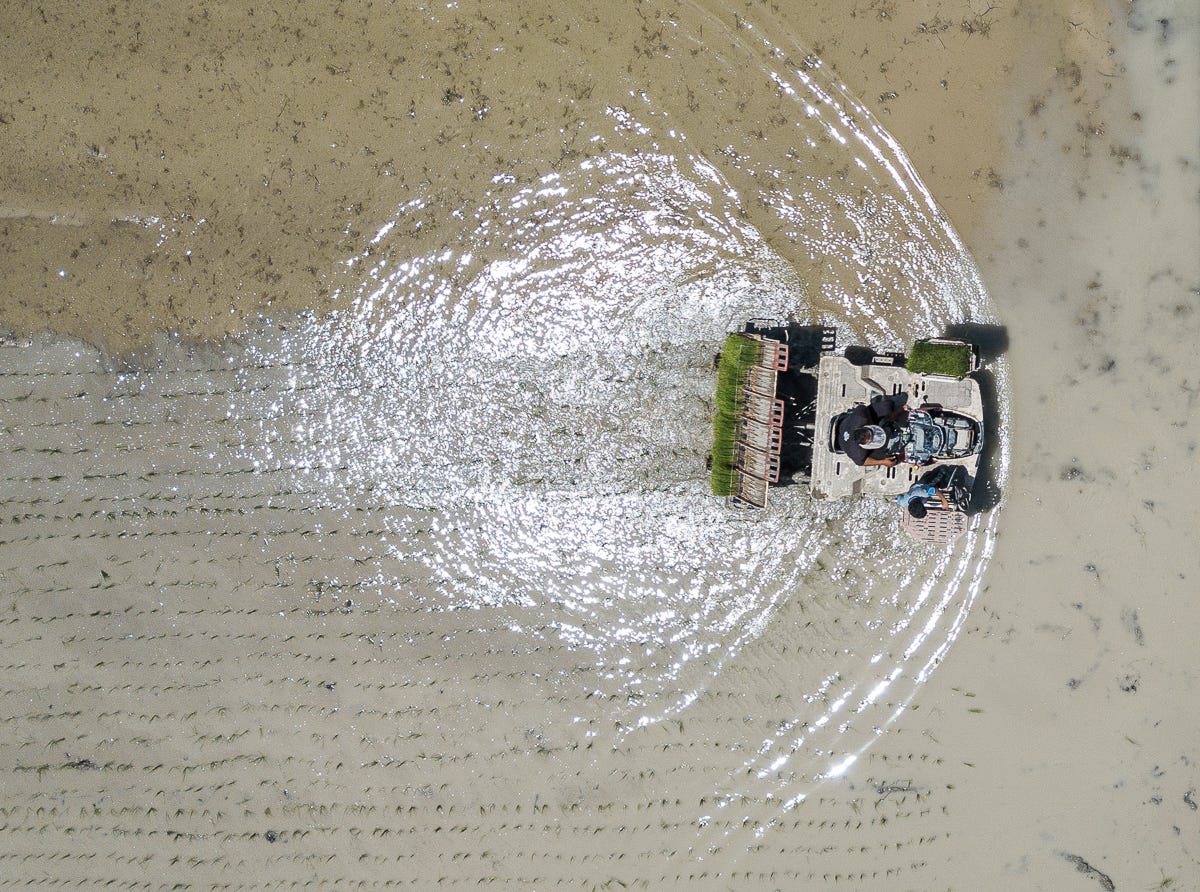

Benham, 30, and all of his brothers are rice farmers in Kamfiruz. After buying a rice planter machine, they work for other field owners, besides planting their own farms.

Behnam is planting rice before the mid-day heat gets to its highest point.

It is 2pm, the hottest time of the day. Behnam and his colleagues are eating lunch, under a small shelter.

Those who do not have a shelter rest in the shadow of their tractor. The temperature reached 37 Celsius degrees on that day.

This year, the winter precipitation was higher than normal, after ten years of persistent drought. Even so, the water resources are still in critical conditions. Although rice planting has been forbidden or severely restricted in the last years in all Iranian provinces, except the ones besides Caspian sea, over 10 thousand hectares of fields in Kamfiruz are flooded to be rice planted this year. Governmental organizations blame farmers that are not willing to change the crop to less water consuming ones due to high profits of rice, whereas farmers blame the government that does not have a promising and supportive program for farmers to change to other crops. They see every other crop unprofitable.

8000 liters of water is consumed to produce one kg of rice, due to high evaporation in this region.

In spite of over normal precipitation this winter, Kor River is not enough to plant all fields in Kamfiruz. Some farmers use a water hole, which is illegal.

During a decade of persistent drought, the border of Doroudzan Lake was moving towards the edge of the dam every year. Some farmers used this as an opportunity and followed the lake border to use the coastal fields as their farms. This year their wheat fields went underwater after a winter of higher than normal precipitation. This is a clear example of short-perspective decision making.

Lunch at one of Kamfiruz houses. Although the drought has affected the whole of Iran and the country is facing strong sanctions which have an impact on its import, rice is still the dominant crop in the Iranian family food.

Kor River is in a fragile situation in the new climate. The left photo shows the river in July 2018 in Kamfiruz Plain. The right photo is taken in July 2019, where the water is streaming again in the river after the good winter precipitation. Even this year, all its water is consumed before Doroudzan Dam, and nothing reaches the fields after the dam. In the following part of the story, we will see the situation in Korbal Plain, which is only 100 km down the river, but the life is extremely different.

Korbal Plain, July 2019. This is one of the dozens of abandoned villages in the area. The fields in the background are a part of 14,000 hectares that were rice fields before the persistent drought began, and they are all arid. The water channel that passes through the picture is one of the 108 channels branching from Kor River, and now it is dry. The villages in this area were home to 50,000 people before the drought.

Houses have gradually been destroyed after people migrated. The doors and windows are taken away to be used or sold.

4,000 out of 8,000 villages in the Fars province have been inhabited until spring 2018.

The abandoned school of the village. 700 students were studying there before.

A music advertisement for the name of a band on an oil tanker which was bringing fuel to the village.

After the higher than normal precipitation of this winter, some farmers who had migrated from Korbal and were living on the outskirts of cities are back to plant their farms. Running or underground water is still not enough for wheat or rice, so they are planting safflower. Safflower looks like saffron without its taste or smell, so it is used by some bakeries as a cheap substitute for saffron. Some saffron producers also buy it from farmers to mix it in their products.

Fardin, 16, has moved to the outskirts of Shiraz with his family. He is back to Korbal after his school this year to help his family harvest flowers. He dreams of becoming a nurse in the future.

Fardin’s mother, who is 60 years old and has five children, is suffering from asthma. Even so, she is back to her farms to harvest safflower this year. Each person collects around 1 kg of safflower per day and sells it for 30,000 tomans (2 euro) to the mediators. Their family has a 4 million tomans (267 euros) debt to the government for farming, which is hard to repay with their current income.

The destiny of nature and people in all areas of the riverbank of Kor has not become like Korbal yet, but all are vulnerable. The first photo was taken in July 2018 in Kamfiruz Plain. The water hole of the farm was dry, and the rice field could not survive. Some people of Kamfiruz had started migration, like the people of Korbal. The second photo shows how lively the rice fields became at the same area in July 2019. All those people were happily back to Kamfiruz, and all fields were planted. Long-term predictions and scientific simulations show that such a fruitful year is an exception not the norm, and the right thing to do is to adapt to the new drier climatological normal. But will a long-perspective holistic view finally find a way to the nature-environment relationship?

Thank you. The number of abandoned villages is chilling